ZEITGUIDE TO AMERICAN ART

Sometimes looking back tells us where we are headed.

“America Is Hard To See,” the inaugural exhibition at the Whitney Museum’s new building in lower Manhattan, does just that. Its survey of 20th century American art offers potent and provocative ideas for those of us wrestling with the 21st century.

Take, for example, the artwork from 1914 through 1950—a period of rapid technological advances. Americans’ understanding of time, work, communication, commerce and leisure all changed in those 35 years, and artists grappled with these transformations. The parallels to today are unmistakable.

Here are just a few of the salient themes that grabbed us. “America is Hard to See” closes September 27th, so if you haven’t seen it and are in NYC, time is running short.

CULTURAL COLLISION

James Daugherty’s Three Base Hit (1914) uses the tools of Italian Futurism to capture a sense of speed, overlapping action, and multiple points of view in one image. Max Weber’s The Chinese Restaurant (1915) applies French Cubism to similar kaleidoscopic effect and depicts an urban American landscape being remade in disorienting fashion by immigration. George Tooker’s The Subway (1950) does not have one person with a smile on his face—also suggesting alienation and claustrophobia of urban life. The surreal Terror in Brooklyn (1941) by Louis Guglielmi adds another interpretation, depicting a group of nuns in a glass bubble with expressions of fear. Is it the gritty city, or the looming war, or something totally subjective that has them terrified?

Today our cities are expanding and transforming much like a century ago, for better and worse. There are new manifestations of our fractured experience and the overwhelming nature of urban life: Uber, one-click everything, mobile phones splitting our attention. Our dependence on technology can also stunt personal interactions and leave us as hardened and isolated as Gugliemi’s nuns or Tooker’s commuters.

SOCIAL UNREST

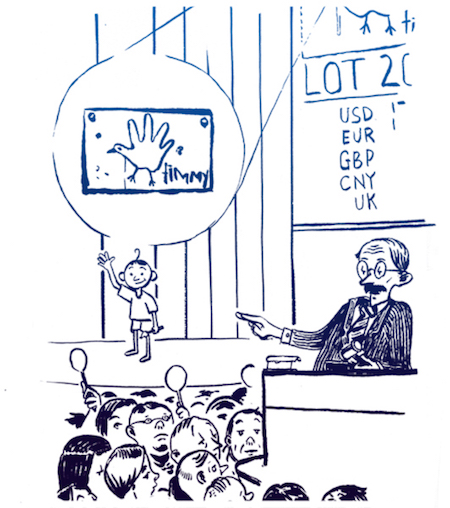

After the stock market crash of 1929, artists documented America’s struggles in all forms of media. Some pieces outwardly supported FDR’s New Deal, others reflected a wariness about American capitalism and militarism, including Bernarda Bryson Shahn’s A Mule and A Plow (1935-6); Mabel Dwight’s Merchants of Death (1935); and Jacob Lawrence’s War Series: Beachhead (1947). Other pieces such as Philip Guston’s Drawing for Conspirators (1930) of a KKK lynching and Ben Shahn’s The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti (1931-32)address ethnic discrimination and victims of a corrupt justice system.

We still grapple with these issues whether it’s the recession, the roller-coaster stock market, or the ongoing concerns expressed by #blacklivesmatter.

ENTERTAINMENT & ESCAPE

When the going gets tough, maybe the tough get going. But most people look for some relief. A whole section of the exhibition is devoted to artworks about forms of escape, from nightclubs to movie theaters. Many of these pieces capture a dark side of entertainment: the brutality of sports (George Bellows’ Dempsey and Firpo [1924]), an elicit encounter in a club or under the cover of night (Paul Cadmus’ Sailors and Floosies [1938] or Charles Demuth’s Distinguished Air [1930]).

These works reveal how blurry the lines are between the real and the imagined, the familiar and the unsettling, the cultural mainstream and the underbelly. One can easily imagine the same dark interpretations of football, Tinder, virtual reality, and the multitude of vices the Internet makes available.

Now that you’ve completed Art 101, you might be wondering: what’s the lesson here?

To a certain extent, it’s that the more things change the more they stay the same. But also that books, movies, art exhibitions, and music help us contextualize and reflect on our current circumstances.

The curators behind “America is Hard to See” offer not only a terrific survey of 20th century art, but also a piercing tour of what is on America’s mind today.