ZEITGUIDE TO DISRUPTING “DISRUPTION”

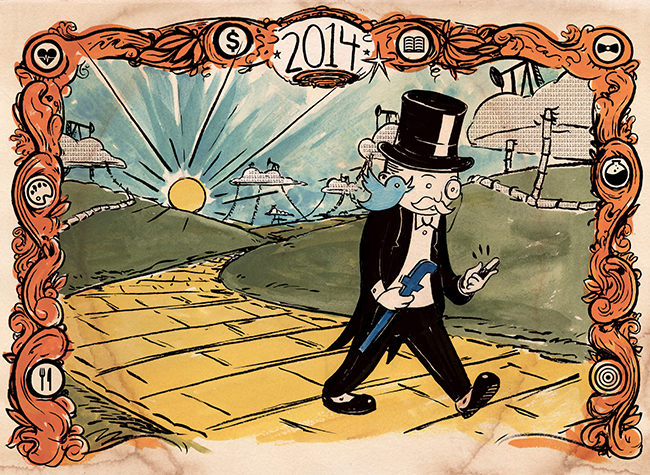

ZEITGUIDE “DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION” IMAGE BY KRISTOFER PORTER

Disruption had a good run as a buzzword, until this week. Which makes us believe that its shelf life may soon end.

There is no doubt that disruption has been overused—like “synergy” was in the 1990s—to the point of meaningless. And Jill Lapore’s recent much talked about New Yorker piece, “The Disruption Machine,” may be the nail in the coffin.

She dismantles the history of disruption theory in business (beginning with the work of Clayton Christiansen, author of the 1997 book “The Innovator’s Dilemma”)—but saves plenty of whacks for how disruption has been applied as a religion among startups.

Christiansen defined “disruptive innovation” as “a process by which a product or service takes root initially in simple applications at the bottom of a market and then relentlessly moves up the market, eventually displacing established competitors.” It defined a risk, a threat—innovation from small guys that could eat into your bottom line. For big companies, then, the message was: disrupt your own business before someone else does.

But it has spread, Lapore suggests, too far and too wide: “Innovation and disruption are ideas that originated in the arena of business but which have since been applied to arenas whose values and goals are remote from the values and goals of business.”

She also suggests that an obsession with disruption has contributed to an irrational moment in the world of business startups. She cites with words of startup investor Josh Linkner, who backs “the next generation of innovators who are, as I was throughout my earlier career, dead-focused on eating your lunch.”

But the truth is, disruption isn’t actually a business strategy that guarantees success—which might be one reason researchers peg the failure rate of startups at 75 percent.

Just this week, Aereo, a company that topped many “Most Disruptive Companies” lists, got shot down by the Supreme Court. Aereo was a legitimate disruptor: its model of streaming individual TV broadcasts to internet devices disrupted the networks so much that they sued for copyright infringement. Yet, in ruling Aereo illegal, the Supreme Court justices relied on how similar Aereo is to the traditional cable TV model, which would make it have to follow the same rules.

People—not just companies—appear tired of getting disrupted. In the San Francisco Bay Area, residents are fed up with tech-fuelled housing prices and private shuttle busses to Silicon Valley campuses. Google’s I/O conference was interrupted by two protestors just days ago, one who claimed to have been evicted from an apartment building Google’s staff lawyer bought.

In Zeitguide 2014, we mentioned Adrian Wooldridge of The Economist’s prediction that in 2014, the tech elite will join bankers and the oil industry in being demonized by the public. If that comes to pass, a contributing factor may be that disruption is about fear, and who wants to be paranoid all the time?

It’s time to start talking about startups for what they create, not what they disrupt. Why not use more positive words like “opportunity” or even “transformation?”

Businesses – both legacy and emerging – have tools today and opportunity sets that have never been available to us before.

That’s not disruption. That’s growth.

Keep Learning,

Brad Grossman

Creator, ZEITGUIDE

Founder, Grossman & Partners

__________________________

Our ZEITGUIDE weeklies continue the conversations we published in our ZEITGUIDE 2014, which you can get here. They explore and guide you through the leading edge issues affecting our constantly changing culture, and therefore, our businesses.